Protein. Carbohydrates. Fat. Calories. That’s how we’ve been taught to think about what we eat. If we can only find the magical mix of macronutrient percentages, we’re told, we can achieve the health and aesthetic goals we’re after. Provided, of course, we stay within the upper bounds of our caloric intake limits.

There are many problems with this thinking, and I won’t address them all in this post. What I want to point out is how thinking about the individual nutrient components of our food (Nutritionism, as Michael Pollan likes to call it), removes eating from its context. It forces us to lose sight of where our food came from, how it was prepared, and how we feel before, during, and after we eat it. If we’re not thinking about these relevant aspects of eating, we can easily be led down a path to poor health.

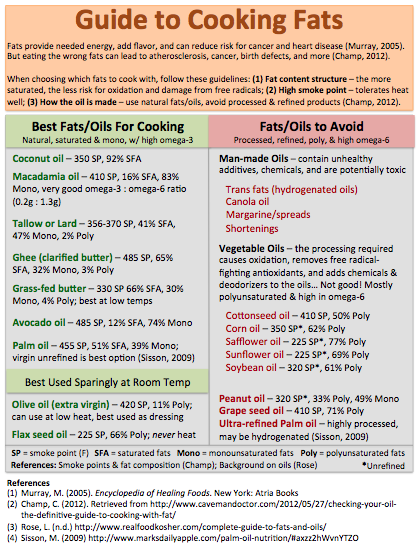

Food preparation is an especially fertile breeding ground for questionable dietary practices. Specifically, the fats we choose to cook with are often misunderstood, and their health benefits and drawbacks underestimated. Most of us have ingrained knowledge (or at least habits we follow) guiding which fats and oils we choose to cook with. Our intentions are good, but are the decisions we make based on sound principles?

The goal of this post is to give you a measuring stick you can use to find out. These three simple guidelines will ensure you’re cooking with the right fats:

- The more saturated the better

- Choose fats with a high smoke point

- Use natural fats and oils

Remember, healthy fats are essential for humans to thrive. Leave the Food Pyramid behind, and think about eating fats within the context of real, whole foods, as well as our evolutionary history.

3 Rules For Choosing Cooking Fats

1) The more saturated the better

The more saturated the fat, the more “stable” it is. This means it won’t break down as easily when exposed to heat, light, and air. By definition, a saturated fat is one whose fatty acid chains cannot incorporate additional hydrogen atoms. The long carbon backbone of the fat is completely saturated with hydrogen. This gives the fat more physical structure, which is why saturated fats like butter and coconut oil are solid at room temperature.

This stable backbone protects the fat from oxidation and free radical damage while cooking. Since all the carbon atoms on the fat are already saturated with hydrogen, the free radical cells have nowhere to bind onto the fat. This is why saturated fats are more stable – their saturation protects them from damage by free radicals.

Polyunsaturated fats, like those comprising vegetable oils, are much less saturated with hydrogen atoms, making them more susceptible to oxidation and free radicals. This is also why vegetable oils typically have a much shorter shelf-life; not only are they more prone to damage at cooking temperatures, but they can hardly hold up to minimal light and oxygen exposure. (See #3 below for more on the dangers of cooking with vegetable oils)

In short, the more saturated the fat, the better. Just remember to source your animal fats (butter, ghee, lard, etc.) from grass-fed, pastured animals. The chemicals and hormones used in conventional farming get stored in the animal’s fat, so consuming butter from an industrially raised cow is definitely not a good idea.

2) Choose fats with a high smoke point

The smoke point of a fat or oil is the temperature at which it gets broken down into its chemical components and begins to emit smoke. Think of the oil at this point as damaged goods. The fat’s component parts become cancer-causing chemicals, and the fatty acids inside the fat becomes damaged through oxidation (releasing more free radicals).

Even the most stable fats become damaged at a high enough heat, so it’s a good idea to choose fats and oils that can tolerate the highest temperature possible. Use this Mindful Caveman Guide to Cooking Fats as a cheat-sheet to determine the smoke point for various oils.

3) Use natural fats and oils (avoid the processed, man-made variety)

Can you crush a kernel of corn on your kitchen counter and produce oil? No, you can’t. The same goes for soybeans and sunflower seeds (two plants commonly used to create vegetable oils). This is a good clue that it takes a tremendous amount of industrial processing at high heat to produce oil from vegetable seeds. We already know high temperatures cause oxidation and rancidity, and since the resultant oils from vegetables are primarily polyunsaturated fatty acids (the least stable kind), they are most susceptible to free radical damage. As a result, vegetable oil manufacturers add color, flavorings, deodorizers, and chemical preservatives to the oils, meaning you actually end up consuming something more closely resembling a science experiment than simply a by-product of vegetable seeds.

Want more background on vegetable oil production? Caveman Doctor does an excellent job explaining the details in this post, and the Food Renegade blog debunks the myth of canola oil as a health food.

Trans fats are also found in many vegetable oils, and should always be avoided. While their negative health implications are well-documented and include inflammation, artery damage, and several cardiac diseases, they can be hard to avoid. While the American Hearth Association recommends limiting daily trans fat consumption to <1% of daily calories, the Food and Drug Administration allows manufacturers to label foods containing <0.5 g trans fat per serving as 0 g trans fat. Since manufacturers control the serving size on food labels, many alter the number of servings per package so they can label the product “trans fat free,” despite the presence of trans fats within the product.

A 2010 study reviewing trans fat consumption in the U.S. puts the dangers of this practice succinctly,

“Many products with almost 0.5 g trans fat, if consumed over the course of a day, may approximate or exceed the 2 g maximum as recommended by American Heart Association, all while claiming to be trans-fat free. Accordingly, greater transparency in labeling and/or active consumer education is needed to reduce the cardiovascular risks associated with trans fats.” (Remig et al., 2010)

Sneaky, sneaky. Since consuming trace amounts of trans fats is nearly unavoidable in Western countries (these oils are commonly used in restaurants and packaged foods), it’s important we don’t add to our daily load when cooking at home. Avoid man-made fats, and use natural oils instead.

Summary

Follow these guidelines when cooking with fats, and you’ll protect yourself from the harmful effects of free radicals and industrial processing, while gaining all the great taste and health-promoting goodness of healthy fats. To recap,

- Cook with saturated fats and oils (from sustainable sources)

- Favor a high smoke point

- Avoid unnatural and processed fats.

Below are a few fats you may want to use, as well as a few you should avoid.

Consider cooking with:

- Coconut oil

- Macadamia oil

- Pastured Tallow or lard

- Grass-fed butter

- Grass-fed ghee

- Olive oil (low-heat, best used as a dressing)

Avoid:

- Canola oil

- Margarine/spreads

- Corn oil

- Soybean oil

- Peanut oil

- Safflower oil

Happy cooking!